- Editorial

- I. Why do we want to think humans are different?, Colin A. Chapman, Michael A. Huffman

- II. "Animal", Jeff Sebo

- III. The Trouble with Liminanimals, Philip Howell

- IV. The Global Pigeon, Colin Jerolmack

- V. From Over the Horizon: Animal Alterity and Liminal Intimacy beyond the Anthropomorphic Embrace, Richie Nimmo

- VI. Time to rethink the law on part-human chimeras, Julian J Koplin, Julian Savulescu

- VII. Queer Liminal Animals, Sacha Coward

- VIII. The Spiritual Ecology of the Shepherd, So Sinopoulos-Lloyd

- IX. AMANDA PARADISE: Resurrect Extinct Vibration, CAConrad

- X. Animal Architecture: Beasts, Buildings and Us, Paul Dobraszczyk

- XI. Feral Cities: Adventures with Animals in the Urban Jungle, Tristan Donovan

- XII. At Home in Other Skins, in Other Formations of my Body, Ama Josephine Budge

- Imprint

VII. Queer Liminal Animals

- Sacha Coward has worked in museums and heritage for over 10 years. For the past three years, he has been freelancing as an historian, public speaker, and researcher. He has run LGBTQ+ focused tours for museums, cemeteries, archives, and cities around the world. He has made several appearances on Virgin Radio, speaking on topics such as Turing’s Law and the history of the rainbow flag. He hosted the sell-out ‘Dragged Through History’ event featuring drag queens from UK’s Drag Race such as Sum Ting Wong, Tia Kofi and Divina De Campo. During Lockdown he worked on the #MuseumFromHome movement on twitter creating daily 60 second videos about history and collections, as featured in Forbes, The Metro and the BBC's Culture in Quarantine series. Sacha Coward has written articles for publications, including Metro, Gay Star News, National Theatre, Art UK, Queer Bible, Royal Museums Greenwich, and Dig It Scotland. His first book Queer as Folklore will be released in August 2024.

“Then your tail will divide and shrink until it becomes what the people on earth call a pair of shapely legs. But it will hurt; it will feel as if a sharp sword slashed through you. Everyone who sees you will say that you are the most graceful human being they have ever laid eyes on, for you will keep your gliding movement and no dancer will be able to tread as lightly as you. But every step you take will feel as if you were treading upon knife blades so sharp that blood must flow.”

Hans Christian Andersen (1837)

Amongst queer gatherings around the world, be them radical or corporate, you are liable to see a number of things. Obviously there will be rainbow flags, progress flags, symbols connected to lesbianism, bisexuality and transgender identities. But alongside this you will always find mythical creatures…

The aesthetics of 2024 queerness is laced with mythical allusion; becoming a secondary set of symbols that LGBTQ+ people use with ease, almost without knowing why they are using them. The monstrous and otherworldly have entered into the queer lexicon on both a conscious and subconscious level.

This has become my obsession for the past few years. I am a queer historian and have been working in museums around the world for over 10 years now, with a particular interest in the stories that have fallen through the cracks. Stories of people like myself, those who have lived and loved differently. Through studying the connections between queer people throughout history and folklore itself, I have started to see a pattern and it is this that inspired me to research and write ‘Queer As Folklore’. This is my first book which explores the role and significance of LGBTQ+ people and the stories we find ourselves enmeshed with.

One of the primary connections I have found relates to the status of mythical creatures and real world queer humans, both existing outside or in between accepted rules of society. Both are liminal animals.

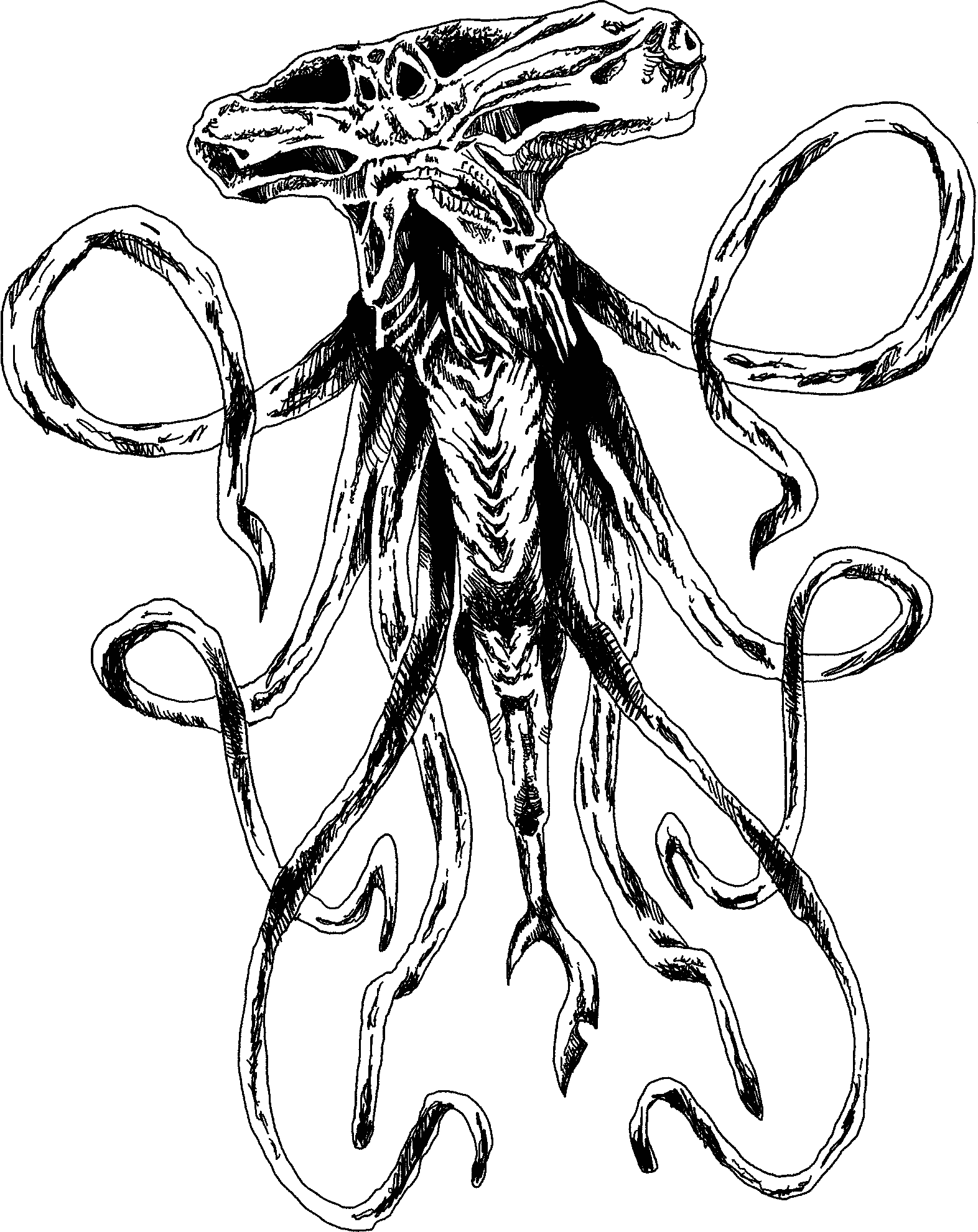

The majority of mythical creatures are at their core some kind of hybrid, meaning they combine elements of different creatures; horse and human, human and wolf, lion and scorpion etc. These mixed-up creatures that have become so connected to the queer experience are therefore by their very nature ‘liminal’, they exist in an in between state of flux and change. This is the umbilical chord that connects queer humans with equally queer creatures.

As an example let’s begin with the mermaid. The mermaid is one of the most ubiquitous mythical creatures, in that almost every society that lives near a body of water has constructed beings akin to mermaids. The majority are not exact body-doubles of the likes of Disney’s Ariel (half fish from the waist down and half light-skinned woman up top) but they all take the human form and remix it in some way with aquatic animals. This creates an interesting internal conflict in the mermaid, between the domains of land and water, as well as the often (but not always) beautiful humanoid maiden and the ‘strange’ and ‘sexless’ sea creature of the lower half. Mermaids are often creatures that trick, can shift their form, and pass as human through magic or mimicry, which again creates a liminality in them, an innate changeability.

World mermaids are in fact a broad category, and they have been spoken into existence long before the golden age of animated cinema. In Australia indigenous people spoke of ‘yawkyawks’ living in freshwater billabongs arguably from their arrival at least 60 thousand years ago. Whether these indigenous mermaidlike creatures were genderbending or ‘queer’ remains to be seen, although there is evidence that many were. Arguably the Peruvian god Sirenx, as described by indigenous performer Rafael Montero, was nonbinary (neither male nor female, and also both). They would bless the musical instruments that performers left near the water overnight. Therefore even those mermaids described only through oral tradition (much of which has been lost due to colonialism) may also have resonated with people who today might have described themselves as queer. These creatures, just as their western offspring, are connected to queerness through their liminal state.

Fast forwarding to the ancient Greeks and Romans there are allusions to mermaids, sirens and aquatic deities being linked with the life of the lesbian poet Sappho. A poet who in some accounts drowned herself and then is resurrected through the often eroticised image of a fish woman and her attendants. Elsewhere in what are now Syria, Palestine and Israel, were once great temples built to a mysterious fish goddess called Atargatis. She was attended to by priestesses who were assigned male at birth. These genderbending mermaid priestesses would go to into ecstatic chanting, dance with rattles and wear long flowing robes and perfumed wigs. In all cases the mermaid, a water/earth spirit that changes and shifts, is connected with people who also shifted between sex and gender norms. In both the tragic story of Sappho and of the woman who would become reborn as the goddess Atargatis, the mermaid also operates in a state somewhere between life and death.

The classical mermaid was then reinvented over and over again in many more guises, but seems to be a favoured symbol for queer artists, writers and poets. From the paintings of Evelyn de Morgan who depicted her muse Jane Hales repeatedly in her painting ‘Sea Maidens’ to the ‘Fisherman and his Soul’ by Oscar Wilde. Both Evelyn and Oscar were inspired by perhaps the most famous mermaid story in the west, ‘The Little Mermaid’ by Hans Christian Andersen. Hans himself created the fairytale after being rejected by a man who he professed deep and heartfelt romantic and sexual desire. He created his half-formed voiceless protagonist arguably as a representation of his own queer heartbreak. The fishwoman who belongs nowhere, exists outside of the norms of human love, would be a natural conduit for his own feelings.

From then on we have a parade of more contemporary queer reinventions by the likes of Noel Coward and most famously, the gay songwriter and playwright Howard Ashman. Howard coproduced the 1989 ‘Little Mermaid’ Disney film. As a gay man he also poured his heart and soul into the lyrics, creating the sea witch Ursula based on 70’s drag queen Divine. In the half woman who could grow legs and live a forbidden life against her father’s wishes, it seems Howard saw something of his own life as a gay man during the HIV pandemic. ‘I want to be where the people are’ is a classic Disney ‘I want’ song, but it takes on deeper meaning when combined with the lives of real humans living equally liminal, dangerous and forbidden existences.

The mermaid from ancient roots, to modern fancy dress is a constructed being that is drenched in the stories of real queer people. Over thousands of years of borrowed and reinterpreted storytelling the half-fish half-woman creature has been taken as a figurehead for so many people whose gender and sexuality would not fit heteronormative society. Today the largest transgender youth support network in the UK takes its name from the mermaid, and drag queens on RuPaul’s Drag Race have borrowed her iconography on multiple occasions for their looks. The mermaid (she, he, they, whatever gendered form is taken) is an unofficial symbol of queerness. Whilst mermaids are often recognised largely for their campness and glitziness, brightly coloured hair, and rainbow scales, this is clearly not all that makes them adjacent to queer people.

It is not just the mermaid that has this connection, in ‘Queer As Folklore’ I have explored all sorts of mythical archetypes from fairies, witches and demons to modern folklore such as superheroes and aliens. All show a similar depth of queer sensibility in their construction and representation, often going all the way back to their earliest recorded mentions. Whilst there are many reasons for this connection, one of the biggest is a shared liminality. This otherness, fluidity and changeability is why the mythical hybrid creature is a natural ‘totem’ for LGBTQ+ people past and present.

The mermaid is a creature of duality. But so is the unicorn, the fairy and the centaur. They are all split, mixed-up creatures, that borrow from the animal kingdom without need to obey the laws of biology or evolution. The result is a creature that is between two normal states, and historically something associated with discomfort and transformation. Humans are often not very comfortable with liminal things, things that are not ‘normal’ or settled. Queer people have often been put into a similar category, being not quite man or woman, or having sex that exists beyond or outside societally acceptable reproductive purposes. Therefore the hybrid liminal creature is a natural match for queer people trying to see themselves.

Liminality also doesn’t just mean in between in form, it can also mean in between time and space. The experience of being queer is nearly always connected with a quest to understand one’s own nature, despite having a paucity of models like you. On discovering that you are gay, or trans, or asexual, due to not seeing people like you represented in everyday culture and society, many LGBTQ+ people will turn to fantasy worlds, escapism and ancient history to find their missing self. Gay men for example have used terms from ancient Greece to describe their desire for other men for hundreds of years at least. Indeed the word ‘lesbian’ is itself a Hellenistic allusion to the poet Sappho’s home of Lesbos. Queer people are liminal in that we exist somewhat outside the time of our birth, we are in some sense time travellers. We have had to root through an assortment of history books, fantastical artwork, myths and legends to find people that reflect our own identities. it shouldn’t be surprising that we also come across the monsters, gods and spirits that populate these worlds.

Liminality is also a source of power, it may be derided and feared but it also the place where in many world cultures magic is born. The idea of ‘magic’ exists in every single culture we know of. The idea that some people can harness or tap into spiritual or unseen forces either by right of birth or through training. Magic can operate within the boundaries of socially acceptable spirituality, but most often it is an outsider. Those who practice magic in societies around the world are not necessarily seen as evil, or dangerous, but frequently are seen as ‘different’ to others. Whether the soothsayer, priestess, sorcerer or fortune teller, there is an air of otherness around these people. Such functionaries are often associated with androgyny and gender bending. For example we know that the Norse concept of ‘seidr’ or magic, was connected with a feminine energy. Men who practised this, even Odin himself, became feminine by association. Within native American peoples we see many examples of third gendered, or two-spirit individuals who operate between or outside male and female roles. These people, such as the Lhamana of the Zuni, are often responsible for magic, storytelling and spiritualism. Our liminality in our lives, loves and bodies allows us to connect with forces that others cannot according to world folklore. Take Hecate the goddess of witchcraft herself, she is associated with crossroads, the very embodiment of liminality and intersectionality. The connection between queerness and magic might therefore explain our historical proximity to otherworldly beings and folkloric creatures through yet again, shared liminal status.

Liminality also gives us access to places that exist outside ‘normal’ society, and allows us to connect to other groups living at the edges of the map, where the dragons dwell. This kind of liminality might also tie and connect us to the mythical monster. On one hand queer people are more likely, irrespective of birth privilege; to mix in secret spaces. Historically due to seeking safety and community, queer folk have rubbed up against migrant communities, artistic groups, criminal societies, sex workers and underclasses. Even a wealthy gay man or woman might find themselves, out of necessity finding a safe space, amongst other people living at the edges of their culture. This would allow for a sharing of storytelling, and ideas between these communities. A storyteller is often perceived to be a traveller and a collector of other people’s experiences, queer people often exist in this transient ‘space which can break down political and societal norms. Some of this can be seen in the kinds of stories we tell, and our interest in ideas, symbols, and creatures that subvert everyday society.

But in being liminal creatures LGBTQ+ people often break societal laws simply through existing. In storytelling, most obviously in fairytales and cautionary tales, there are clear lessons embedded which teach the reader morality, or at least how their society believes they should behave. Therefore the monster, be it a mermaid, a werewolf or a vampire, is often a teaching tool about the danger of breaking social codes; Don’t have sex out of wedlock, don’t wander into the forest with strange men, don’t be vain etc. Queer people are therefore most frequently represented in moralistic narratives as the strange creature out in the forest, and not as the hero or heroine. The way we live, love, dress and behave transgresses, and therefore we are often the inspiration of these creatures, not always explicitly but often as a subtext. When hunting for cultural archetypes that we can see ourselves in, the monster or the hybrid is often easy to connect with, as they are often associated with heterosexist anxieties around deviant sex and promiscuous behaviour. To be ‘other’ ‘outside’ ‘half formed’ and ‘in between’ is to see yourself more in the dragon than the brave prince or damsel in distress.

Overall in researching the queer connections to mythical creatures of all shapes and sizes I have seen a connection that is in fact very human despite its subject matter. The creators and custodians of folklore around liminal hybrid creatures, as well as the liminal spaces that birth magic and superstition, are frequently aligned with character traits and lifestyles that today we can call queer. Gay, lesbian, transgender, intersex and asexual people crafted these tropes, and were also represented by them because of their own liminal natures. The history of the mermaid, vampire, witch and robot is rich with gender bending and homosexual desire. In short the history of the hybrid monster is also the history of hybrid people. Queer people; People that shift, blend and remake themselves in secret spaces.

Liminality is often a trait that is hated, cursed and punished, but it is also a place of significant strength and fascination. There is a reason children dress up as monsters for Halloween, and why my favourite character of Disney’s Little Mermaid was the six-legged octopus witch and not the beautiful protagonist! We are drawn to liminal creatures, even strange and dark ones, as I think we intrinsically know they have untold power. This is something I see us unlocking in ourselves as queer liminal human creatures, despite society’s intolerance and often outright hostility; The mermaid in Andersen’s story is gifted cursed legs, they hurt to walk on, and yet she dances so beautifully.