- Editorial

- I. Why do we want to think humans are different?, Colin A. Chapman, Michael A. Huffman

- II. "Animal", Jeff Sebo

- III. The Trouble with Liminanimals, Philip Howell

- IV. The Global Pigeon, Colin Jerolmack

- V. From Over the Horizon: Animal Alterity and Liminal Intimacy beyond the Anthropomorphic Embrace, Richie Nimmo

- VI. Time to rethink the law on part-human chimeras, Julian J Koplin, Julian Savulescu

- VII. Queer Liminal Animals, Sacha Coward

- VIII. The Spiritual Ecology of the Shepherd, So Sinopoulos-Lloyd

- IX. AMANDA PARADISE: Resurrect Extinct Vibration, CAConrad

- X. Animal Architecture: Beasts, Buildings and Us, Paul Dobraszczyk

- XI. Feral Cities: Adventures with Animals in the Urban Jungle, Tristan Donovan

- XII. At Home in Other Skins, in Other Formations of my Body, Ama Josephine Budge

- Imprint

XII. At Home in Other Skins, in Other Formations of my Body

- Ama Josephine Budge is a Speculative Writer, Artist, Curator and Pleasure Activist whose praxis navigates intimate explorations of race, art, ecology and feminism, working to activate movements that catalyse human rights, environmental evolutions and troublesomely queered identities. Usually based in London, Ama can be also found in Accra, or New York City.

Island

What does it mean to be born an island?

They say we are contrary by nature: ever moving, ever-anchored, ever lost. Always entirely unmappable. But we think this myth is born of a species that do not understand duality; fluctuation; tides; flow.

In YtiliBissộp all the islands are sentient.

We weren’t always. For almost an age, we forgot that we could talk. That we could scream. So, when they burned our backs and picked away at our flesh with iron needles like a thousand rotting splinters, when we were suffocated with a greying second skin, even when they poured their excess into the oceans until our very fingers were burned, bleached and crumbled away; we were silent. We forgot that we could cry out. Could rise up. Could fight back.

We forgot that we were sacred.

It was not a simple thing, this forgetting. Not a trick of time or a predisposition toward infirmity, not a cost of age, nor a flood of universal inconsequence. It was a deliberate act. It was done to us. Slowly, over millennia, so that we no longer knew that which we know. So that we were no longer even ourselves, and no longer wanted to be much of anything, if it could be said we wanted at all.

Oh, how we loved them when first they landed on our shores in their gleaming metal wombs. They spoke with us in reverence, in awe and admiration. We shared stories of our travels: things we’d seen, places we had breathed, the tears we’d wept at the bright green of a sunrise, at the birthing of new worlds. Eventually they lay with us too, they taught us pleasures yet undiscovered, they bore us fleshy, two-legged children who carried our names but not our predisposition for memory. Generations changed their blood in a way it could not change ours, and once they saw all that we could be when angered, when risen, they became afraid. And fearful animals are quick to anger, and slow to forgiveness.

But just as seas know not the circumference of sand as they are shaping it, they did not know what the violence of our undoing would do to them. So they forgot the ways of the sea and how to build their metallic wombs, they forgot to read the stars and the sunsets, and how to turn to all sentient life as teachers. In dislocating who we were, they lost themselves as well. And for that heinous crime, we may all pay with our lives.

*

‘For once they intuited that the human will was long intent on capture, they all conspired to rest their Truth everywhere. And in the simplest of things. Like a raindrop. And therefore the most beautiful of things, so that Truth and Beauty would not be strangers to one another, but would reply one on the other to guide the footprints of the displaced, and those who chose to remain put; of those only once removed and those who had journeyed far in the mistaken belief that books were the dwelling place of wisdom; those who thought that the lure of concrete would replace or satisfy the call of the forest; those who believed that grace was a preoccupation of the innocent and the desire to belong a craving of the weak.’

M. Jacqui Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing (2005)

Animal

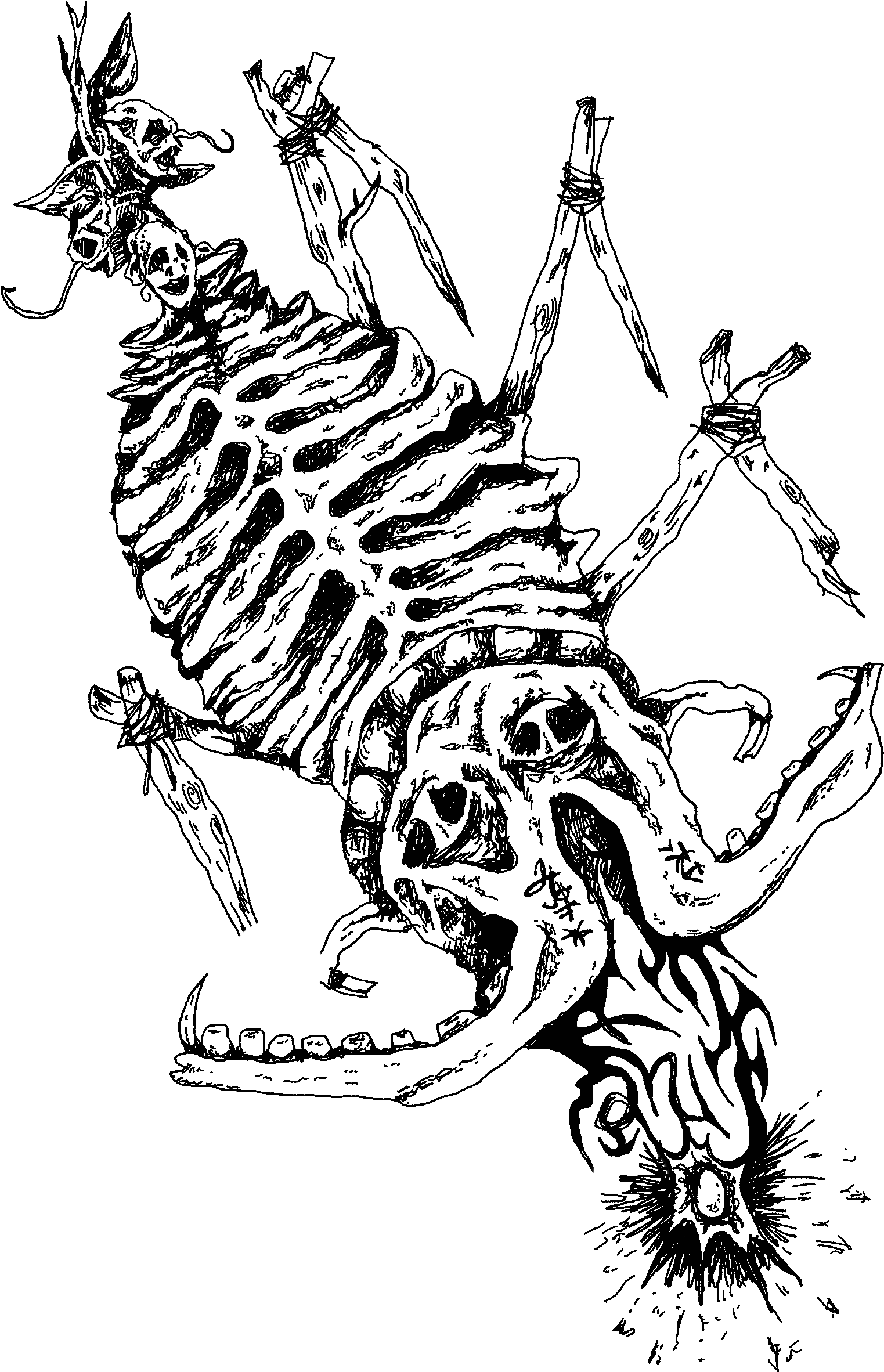

What does it mean to be born an animal?

To feel one’s spine crack upon moving from lack of use, from being forced to stand on only two of our limbs, the others – tentacular follicles of spirit and becoming – stumbling out of rhythm. Untethered. Unbelonging.

Do you know how it feels to coil all your muscles taught, to prepare to leap, to spring, to run, to soar, and then never let loose the motion? Truncated choreographies. Powerful ligaments stagnating and atrophied. Adrenalin running laps around logic. The mantra repeated: you are not safe, you are not safe, you are not safe.

But there is nowhere to go (back) to, my ancestors retrace their steps, but the land has changed now. Become water. Become desert. Become cartographies our bodies did not evolve to survive. We dip exposed bones into pools of salt planes and taste those that came before. They whisper to us the secrets of transformation. But we have forgotten our tongues. We left them with you. The invader. The displacer. The non-animal. You preserved them in vials of liquid and gelatine. Claimed they had magical properties, that they could transport you into the future. Evidence, you said, that time is not a tide but a line.

Back and forth.

Back and forth.

Our hooves crack and splinter on these endless concrete paths, as we walk, and walk, and walk, and walk, seeking the right doorway for entry. Denied. The price is too high. Denied. The cost of my pelt. Of my paws, of my teeth. I would give you my language, if I had not lost it on the road.

The mantra repeated: you are not home, you are not home, you are not home.

Your skins wrapped too tight over my own. The seams, splitting. Revealing unshapely organs beneath. And a rage. A kind of feral loving. A kind of loving back to myself. Back to the animal.

The mantra repeated: you are not enough, you are not enough, you are not enough.

You are almost enough, but not quite.

Yet all these things you fear about us, I love about myself.

Oh, how I have loved my tender monstrosities.

I love the way they make me not you.

Even as there is no you without me,

No me without us,

No us,

without

animal.

*

‘It looked like pictures I had seen of wolves. It was wedged against a hanging boulder just a few steps up the steep canyon wall from us. It moved. I saw its bloody wounds as it twisted. I bit my tongue as the pain I knew it must feel became my pain. What to do? Keep walking? I couldn’t. One more step and I would fall and lie in the dirt, helpless with the pain. Or I might fall into the canyon. […] Then I felt the dog die. I saw it jerk, shudder, stretch, its body long, then freeze. I saw it die. I felt it die. It went out like a match in a sudden vanishing of pain. Its life flared up, then went out.’

Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower (1993)

*A version of the first section of this text, “Island”, was commissioned by Invisible Flock, as part of a larger work for the UK Green Guide, within the Creative Responses to Sustainability’s series of country-specific guides published by the Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF) through its arts website culture360.ASEF.org. The guide was published digitally in 2021, and is still available to view online.