- Editorial

- I. Why do we want to think humans are different?, Colin A. Chapman, Michael A. Huffman

- II. "Animal", Jeff Sebo

- III. The Trouble with Liminanimals, Philip Howell

- IV. The Global Pigeon, Colin Jerolmack

- V. From Over the Horizon: Animal Alterity and Liminal Intimacy beyond the Anthropomorphic Embrace, Richie Nimmo

- VI. Time to rethink the law on part-human chimeras, Julian J Koplin, Julian Savulescu

- VII. Queer Liminal Animals, Sacha Coward

- VIII. The Spiritual Ecology of the Shepherd, So Sinopoulos-Lloyd

- IX. AMANDA PARADISE: Resurrect Extinct Vibration, CAConrad

- X. Animal Architecture: Beasts, Buildings and Us, Paul Dobraszczyk

- XI. Feral Cities: Adventures with Animals in the Urban Jungle, Tristan Donovan

- XII. At Home in Other Skins, in Other Formations of my Body, Ama Josephine Budge

- Imprint

I. Why do we want to think humans are different?

- Colin A. Chapman has conducted research in Kibale National Park in Uganda for 30 years, contributed to the park’s development and protection, and devoted great effort to promoting conservation by helping rural communities. His research focuses on how the environment influences animal abundance and social organization. Given animals’ plight, he has applied his research to conservation. Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, Killam Fellow and Conservation Fellow to the Wildlife Conservation Society, Chapman was advisor to National Geographic and received the Velan Award for Humanitarian Service.

- Michael A. Huffman Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University, publishes extensively in the fields of cultural primatology, animal self-medication, ethnobotany, pharmacology, primate host-parasite ecology, reproductive behavior and physiology, behavioral endocrinology, phylogeography, and historical primatology. He has published on over 15 primates and other mammals in Japan, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, India, Vietnam, China, Bangladesh, Tanzania, Uganda, Guinea, South Africa, and Brazil. He is deeply committed to building bridges through international collaborations and mentoring in over 35 countries.

Humans have the propensity to place things into categories (i.e., good vs. bad, full vs. empty, black vs. white), which can directly shape how we view the world. Since categorization shapes our actions, it is important to evaluate their validity and distinctness and the degree to which one category blurs into the next. One categorization that has intrigued scholars for centuries is that of humans versus nonhuman animals. We often put humans on a pedestal, as unique and superior to all other animals: one of a kind; unlike any other animal. For example, in the 17th century, Rene Descartes stated that only people were creatures of reason, linked to the mind of God, while animals were merely machines made of flesh. His follower Nicolas Malebranche went on to say that animals “eat without pleasure, cry without pain, grow without knowing it: they desire nothing, fear nothing, know nothing.” Today Descartes’s and Malebranche’s statements may seem extreme and wrong (Call, 2006), but they clearly reflect the propensity to see animals and humans as very different and humans as superior.

The view of humans and animals has changed since the 17th century (Fuentes, 2018; Marks, 2016; Van Schaik, 2016), thus these categories need to be reevaluated. Other categorizations have changed dramatically over time, with very positive effects on human societies. When the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Constitution was written, “only white male property holders [were] deemed adequately endowed to be included in the category of personhood” (US 1776). This is no longer the definition of personhood. In fact, the question of whether great apes warrant being accorded personhood is generating much academic interest today (Kurki and Pietrzykowski, 2017; Shyam, 2015; Wise, 2014).

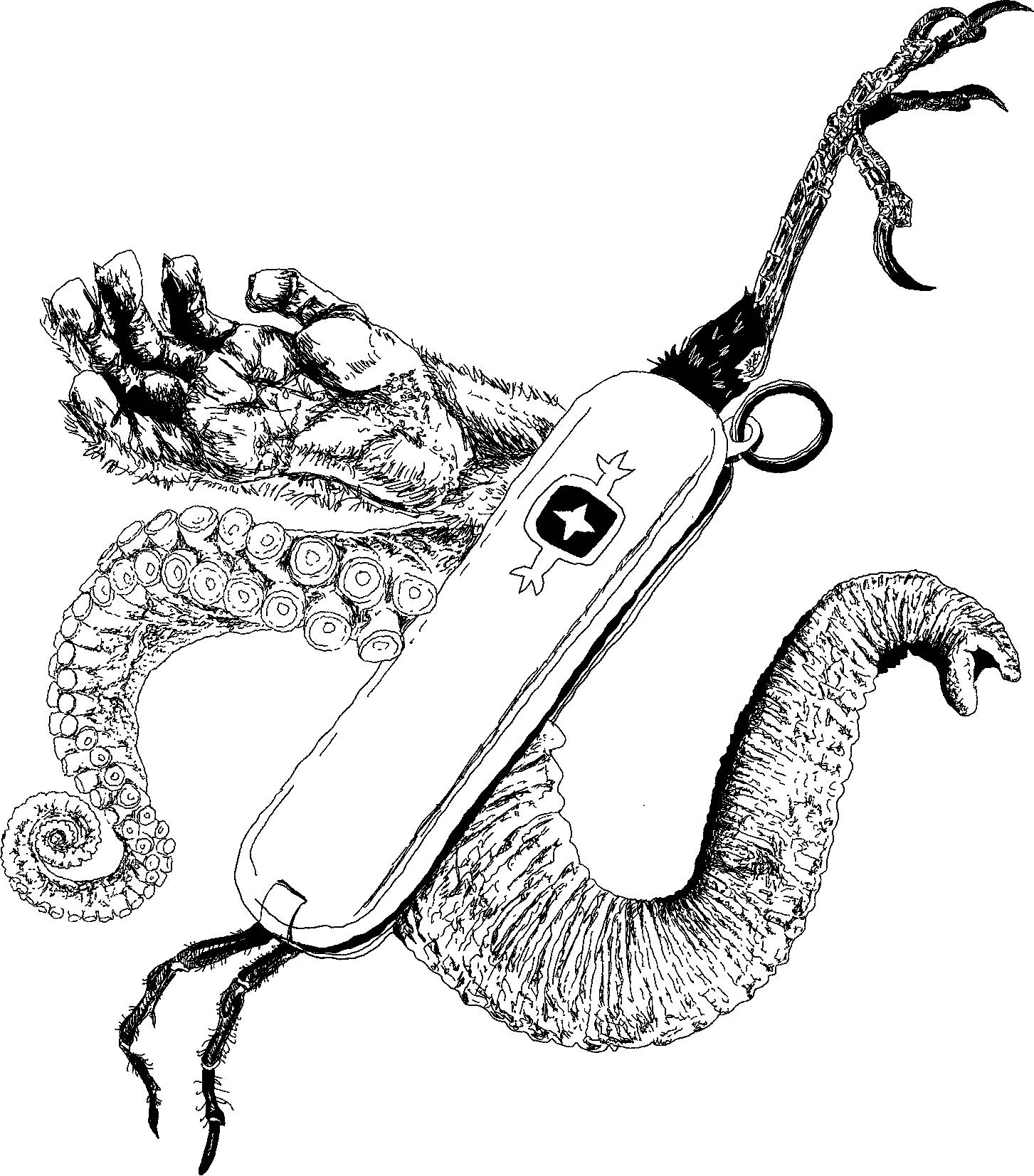

A second reason to reevaluate the human/animal distinction is that many of our previous criteria for human uniqueness have proved wrong. Thomas Carlyle (1833) stated that “Man is a tool-using animal. Without tools he is nothing, with tools he is all” (Carlyle, 1833). This definition of “Man the Tool Maker” was largely viewed as true until the 1960s, when Jane Goodall’s observations of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) using tools to extract termites from their mounds (with the help of publicity from National Geographic) eventually invalidated Carlyle’s definition. It had taken well over a century (Goodall, 1986; Goodall, 1964). Prior to the Goodall findings, there had already been considerable evidence, largely ignored, that the definition was flawed. For example, in 1925 Köhler reported a series of simple experiments that clearly demonstrated chimpanzees could use tools and even cooperate in tool use to obtain food rewards. The chimpanzees would pile boxes one on top of another and then use sticks (even putting two sticks together) to reach a food reward hung high above their heads. Several primate species have now been shown to be habitual tool users, some maintaining tool-using cultures for hundreds of generations (Haslam et al., 2017).

Today we know that tools are also used by many non-primate species such as elephants (Hart and Hart, 1994), Caledonia crows (van Casteren, 2017), African grey parrots (Pepperberg, 2004), sea otters (Hall and Schaller, 1964; Fujii et al., 2014), rodents (Nagano and Aoyama, 2017), octopuses (Finn et al., 2009), and some fish (Bernardi, 2012).

A similar failed criterion had been put forward in 1891 by Sir William Osler, who stated: “A desire to take medicine is, perhaps, the great feature which distinguishes man from other animals.” The subsequent extensive documentation of medicinal plant use by chimpanzees and other primates opened the flood gates for research in this area (Huffman, 1997; Huffman, 2007), leading to examples of medicine use not only by other mammals (e.g., elephants, bears, civets, coatis, porcupines), but also birds (e.g., snow geese, finches, raptors) and insects (e.g., bumble bees, ants, butterflies) (Engel, 2002; Huffman, 2007).

Chu (2014) suggested that humans are unique in their ability to build complex structures. A number of authors have since echoed this (Fuentes, 2017; Marks, 2015) despite the evidence of complex living constructions by animals such as beavers (Castor canadensis), birds, bees and wasps (Doucet et al., 1994; Hansell, 2000; Hepburn et al., 2016). Termite mounds are remarkable structures with specific areas built for different purposes, elaborate features for draining water and cooling the mound, and even gardens to cultivate fungi as a source of food and medicine (Darlington, 1985; Korb, 2003; Korb, 2010).

These and many other such claims about putative defining differences between humans and animals span from 1833 to 2014 have proved wrong. Yet the desire to see humans as unique still remains. Is this a valid scientific question? One of the distinctive features of science is hypothesis testing (Cartmill, 1990; Popper, 1968). If hypotheses about human uniqueness repeatedly prove to be wrong for one trait after another, does this not imply that the hypothesis itself is wrong? We can keep resurrecting the hypothesis with new traits not yet considered, but to what end?

Evolutionary theory is a widely accepted explanation for the diversity of life on the planet. If uniqueness were intended to mean humans are one of a kind, unlike anything else, this would contradict evolution[…]

References

Bernardi, G. (2012) The use of tools by wrasses (Labridae). Coral Reefs, 31, 39.

Call, J. (2006) Descartes' two errors: Reason and reflection in the great apes. In Rational animals? (S. Hurley & M. Nudds, Eds.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carlyle, T. (1833) Sartor resartus (meaning 'the tailor re-tailored'). Fraser's Magazine.

Cartmill, M. (1990) Human uniqueness and theoretical content in paleoanthropology. International Journal of Primatology, 11, 173-192.

Cheng CJ Chu, Ping F Chien, Chou P Hung (2014) Tuning dissimilarity explains short distance decline of spontaneous spike correlation in macaque V1. Vision Research, 96, 113-132.

Darlington, J. P. (1985) The structure of mature mounds of the termite Macrotermes michaelseni in Kenya. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 6, 149-156.

Doucet, C. M., Adams, I. T. & Fryxell, J. M. (1994) Beaver dam and cache composition: Are woody species used differently? Ecoscience, 1, 268-270.

Engel, C. (2002) Wild health. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Finn, J. K., Tregenza, T. & Norman, M. D. (2009) Defensive tool use in a coconut-carrying octopus. Current Biology, 19, R1069-R1070.

Fuentes, A. (2017) Human niche, human behaviour, human nature. Interface Focus, 7, 20160136.

Fuentes, A. (2018) How humans and apes are different, and why it matters. Journal of Anthropological Research, 74, 151-167.

Fujii, J. A., Ralls, K. & Tinker, M. T. (2014) Ecological drivers of variation in tool-use frequency across sea otter populations. Behavioral Ecology, 26, 519-526.

Goodall, J. (1964) Tool-using and aimed throwing in a community of free-living chimpanzees. Nature, 201, 1264.

Goodall, J. (1986) The chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of behaviour. London: Harvard University Press.

Hall, K. & Schaller, G. B. (1964) Tool-using behavior of the California sea otter. Journal of Mammalogy, 45, 287-298.

Hansell, M. (2000) Bird nests and construction behaviour. Cambridge University Press.

Hart, B. L. & Hart, L. A. (1994) Fly switching by Asian elephants: Tool use to control parasites. Animal Behaviour, 48, 35-45.

Haslam, M., Hernandez-Aguilar, R. A., Proffitt, T., Arroyo, A., Falótico, T., Fragaszy, D., Gumert, M., Harris, J. W., Huffman, M. A. & Kalan, A. K. (2017) Primate archaeology evolves. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1, 1431.

Hepburn, H., Pirk, C. & Duangphakdee, O. (2016) Honeybee nests. Springer.

Huffman, M. A. (1997) Current evidence for self-medication in primates: A multidisciplinary perspective. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 40, 171-200.

Huffman, M. A. (2007) Primate self-medication. In Primates in perspective (C. J. Campbell, A. Fuentes, K. C. MacKinnon, M. Panger & S. K. Bearder, Eds.), pp. 677-690. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Huffman, M. A., Gotoh, S., Turner, L. A., Hamai, M. & Yoshida, K. (1997) Seasonal trends in intestinal nematode infection and medicinal plant use among chimpanzees in the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania. Primates, 38, 111-125.

Köhler, W. (1925) The mentality of apes (translated from the second revised edition by E. Winter). London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner.

Korb, J. (2003) Thermoregulation and ventilation of termite mounds. Naturwissenschaften, 90, 212-219.

Korb, J. (2010) Termite mound architecture, from function to construction. Biology of termites: A modern synthesis, pp. 349-373. Springer.

Kurki, V. A. & Pietrzykowski, T. (2017) Legal personhood: Animals, artificial intelligence and the unborn. Springer.

Marks, J. (2015) Tales of the ex-apes: How we think about human evolution. University of California Press.

Marks, J. (2016) Tales of the ex-apes. General Anthropology, 23, 1-7.

Nagano, A. & Aoyama, K. (2017) Tool-use by rats (Rattus norvegicus): Tool-choice based on tool features. Animal Cognition, 20, 199-213.

Osler, W. (1891) Recent Advances in Medicine. Science 17: 170–171.

Pepperberg, I. M. (2004) “Insightful” string-pulling in Grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus) is affected by vocal competence. Animal Cognition, 7, 263-266.

Popper, K. R. (1968) Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientific knowledge. New York: Harper & Row.

Shyam, G. (2015) The legal status of animals: The world rethinks its position. Alternative Law Journal, 40, 266-270.

van Casteren, A. (2017) Tool use: Crows craft the right tool for the job. Current Biology, 27, R1314- R1316.

Van Schaik, C. P. (2016) The primate origins of human nature. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Wise, S. (2014) Rattling the cage: Toward legal rights for animals. Da Capo Press.

This article has appeared in the journal Animal Sentience, a peer-reviewed journal on animal cognition and feeling. It has been made open access, free for all, by WellBeing International and deposited in the WBI Studies Repository. DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1358

Originally published in Animal Sentience 23(1), 2018.