Karakachans in Bulgaria – A Pastoral History

-

Gabriela Fatková

is a social anthropologist. She focuses on the Balkans, where she conducted long-term field research on the social organization of formerly nomadic shepherds – the Karakachans. She works at the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen and is also the editor-in-chief of the journal „Porta Balkanica“, which concentrates on social science research in the Balkan region. Her further areas of interest include the anthropology of gender and the evaluation of quality in higher education, especially the topic of study failure (in relation to distance learning, abuse of power, etc.).

Means of subsistence in the period of transhumant pastoralism

During their period of transhumant pastoralism, the Karakachans made a living herding sheep, goats, and horses. Occasionally they also kept pigs and poultry; however, the principal animal for the Karakachans was the sheep. Over the course of the year, they drove their herds numbering several thousand heads between two types of pasture, taking all of their possessions with them on horse-drawn caravans. They spent the hot summers with their sheep on pastures high up in the Stara Planina, Rila, Rhodope, and Troyan mountains; winters were spent in the coastal lowlands. Later, influenced by the intensification of farming and expansion of tilled land, they were displaced higher into the mountains in the summer and outside the advantageous, arable areas in the winter. They lived alternately in the two types of landscape. However, they considered their home to be the mountain regions where they spent the summer, just as the Yörüks and Karakachans both saw their region of origin as the place where they wintered (Kalionski 2002: 6).

For the winter, they drove their herds onto plains where the weather was warmer and sheep could find places to graze throughout the whole winter. In the period of Ottoman rule, they most often found their summer pasture in Greece and Turkey. Later, after the territory of Bulgaria was separated from the Ottoman Empire in 1878 (which I will henceforth refer to as “the liberation”),1 crossing the Bulgarian–Greek and Bulgarian–Turkish borders became more complicated for the shepherds and they had to choose one state within whose borders they would decide to move throughout the year (Pimpireva 1995: 90). Some groups spent the winter in Anatolia and Eastern Thrace, mainly near the cities of Edirne, Babaeski, Hayrabolu, and Kırklareli (see Fig. 3). During the period of Ottoman rule, all the Karakachans needed for entirely free movement throughout Anatolia and Thrace was a document known as a “nafuz” or “teskere”. After the liberation, crossing borders required passports and many other documents, and high fees had to be paid for herds (Marinov 1964: 29–31; Nešev 1998: 20).

The establishment of borders between Bulgaria and Turkey after the liberation brought with it still more problems: the Karakachans could no longer trade in sheep on Turkish territory. All sheep were counted on the outward journey and registered throughout; on the homeward journey, shepherds were allowed a loss of 10%. If they returned with fewer than 90% of the sheep from their original herd, they had to pay fines for each missing sheep on both the Turkish and the Bulgarian side.

The Karakachans quickly adapted to this situation and simply stopped crossing the Bulgarian–Turkish border, because doing so had become disadvantageous. Some of them stayed on the Turkish side for good and assimilated (Marinov 1964: 29–31). In 1933, the Turkish border became impassable for good. Karakachans who were travelling with their herds to Turkey at that time were forced to turn around at the border and go back. To keep their herds from dying off, they had to sell them off quickly before the winter, substantially below cost. After this experience, many of the shepherds decided not to replenish their herds the next year and transitioned to a settled lifestyle (Marinov 1964:32). Other Karakachans wintered in the so-called “White Sea” region – that is, in Greece, in the lowlands by the Mediterranean Sea (see Fig. 3). The most common wintering sites in Greece were the Strymonian Gulf and the areas around Xanthi, Serres, Drama, Soufli, Kavala, and Salonika (Thessaloniki). During the winter of 1943–1944 the border between Bulgaria and Greece was closed and Karakachans wintering in Greece were forced to remain (Marinov 1964: 31–33).

The year 1944 was critical in many respects. The Ministry of Agriculture started to restrict the movements of the Karakachans, who had to winter at sites allotted to them. They often had to wait a long time for these verdicts with their herds, even after the first frosts came and the herds suffered greater and greater losses (Marinov 1964: 32–33). The closing of both the Greek and Turkish borders caused substantial changes in the Karakachans’ subsistence strategies. Those who remained on Bulgarian territory were forced to accustom themselves to harsher winters that often caught them unprepared, as well as to insufficient pasture, especially during the winter. They had to compensate for the lack of natural pasture by buying feed, the price of which also substantially determined their movements – they mainly travelled, to the extent possible, to wherever feed was cheapest that year.

After the borders were closed, the Karakachans sought new wintering sites within Bulgaria (see Fig. 2). Ultimately, they wintered in approximately five areas. The first area was by the Black Sea coast around cities and towns like Burgas, Nesebar, and Primorsko. Karakachans moved to this area for the winter primarily from the Stara planina and Sredna Gora. The second area was situated around Elhovo, Topolovgrad, and Yambol; the third, above the northeastern tip of the Rhodopes around Haskovo, Kardzhali, Harmanli, and Svilengrad, was a wintering site primarily for the group from the Rila and western Rhodopes; the fourth was around the town of Petrich; and the fifth was in northeastern Bulgaria around Lom, Vratsa, Berkovitsa, and Montana and was the wintering site of Karakachans from the western Stara Planina and Rila. Other smaller groups also wintered in the vicinity of Varna, Kazanlak, Stara and Nova Zagora, Plovdiv, and Pazardzhik (Marinov 1964:32; Pimpireva 1995: 88).

They lived year-round in circular, dome-like huts built from natural materials like branches, straw, and leaves, building one hut for the summer season and one for the winter. During their transfers, they slept under just a simple tent (Urbańska 1962: 219). The huts were approximately 6–7 m in diameter and 4–6 m high. The huts’ frames were woven from thin branches with sheaves of straw fastened to them in rows from the outside. Clay was also sometimes spread across the inside of the hut (Urbańska 1962: 218–219).

The Karakachans’ main source of subsistence during their period of transhumant pastoralism was sheep. They traded in both live animals and dairy products (primarily cheeses) and wool, and they also collected and sold sheep dung. This was a fertilizer valued by farmers in the foothills, some of whom even paid Karakachans during their transfers to spend the night with their herds on the farmers’ fields and thus fertilize them (Marinov 1964: 51). It is thus apparent that almost nothing from the sheep went to waste, and sheep thus represented a truly multifaceted and mobile source of income.

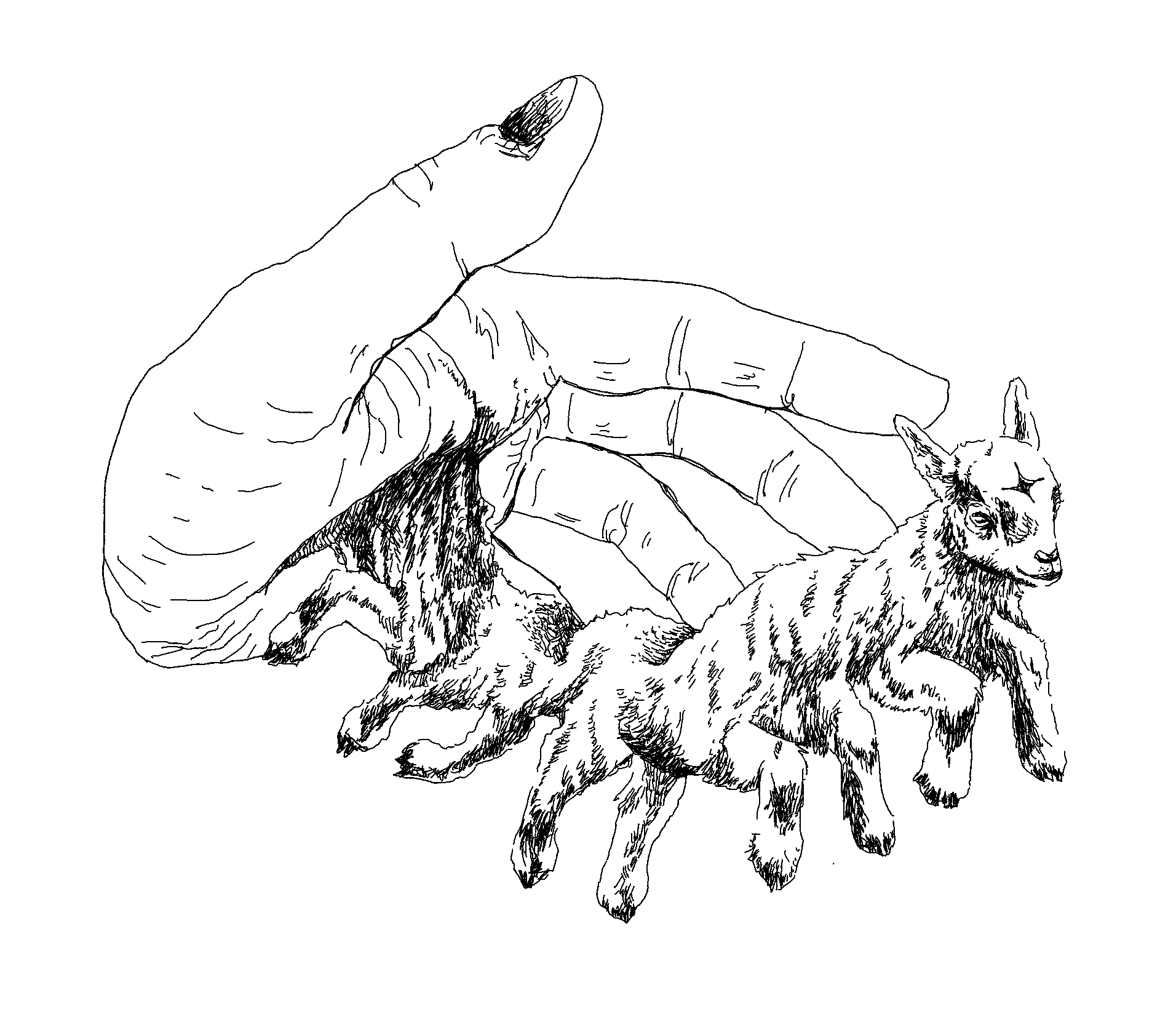

They divided their herds of sheep into three sections. In the first section were pregnant ewes, ewes with the youngest lambs, and dairy ewes. In the second section were barren ewes and rams, and in the third section, grown-up lambs from the previous year (Campbell 1964: 19). They tried to find the best possible pasture for the first group, because the income from the lambs and milk were the most important for the whole group. Lambs are born between November and January, so those sheep always grazed near a settlement. Around February, the milking season began. Lambs were left with their mothers for no longer than four weeks and then sold. Only a few were left in the herd to maintain a balanced proportion of ewes and rams (Campbell 1964: 19–21). The ewes were milked in kosharas (sheepfolds, Fig. 6), special pens by whose exit the milkers would catch ewes one by one and gradually milk them. A Karakachan ewe produces c. 30–32 liters of milk in one season, which is approximately half the amount produced by species of sheep bred for milk; on the other hand, it is very hardy, and the Karakachans benefited above all from the number of ewes they were able to keep (Marinov 1964: 57). Rams and barren ewes – that is, the second part of the herd – typically grazed high in the mountains in poorer pastures, accompanied by a young herdsman (usually an unwed young boy). Slightly better pastures were given to the grown-up lambs (Campbell 1964: 22). Rain shelters were built for the sheep right on the pastures; their construction was, excepting small amounts of male assistance, women’s work, as was the construction of the residential huts (Marinov 1964: 49–51).

While the Karakachans had access to winter pastures in Greece and Turkey, grazing was often sufficient throughout the year, but in harsher winters, they were forced to supplement their animals’ diet with purchased hay and grain. After they limited their routes to the territory of Bulgaria, buying feed (hay, corn, barley, rye, oats, sugar beets) became an annual necessity. Even in the previous period, they had to buy salt throughout the year for sheep, goats, and horses (Marinov 1964: 52–56).

The Karakachans either processed the milk themselves at home and then sold the final products, or left this to specialized cheese producers. These dairies were irreplaceable primarily in the production of yellow cheese known as kashkaval, which was not economically feasible to manufacture in small amounts. The Karakachans themselves had several alternative types of durable cheese, so kashkaval was not a crucial product for them (Marinov 1964: 58–67). The dairies were either temporary or permanent. They were typically built in the vicinity of a water source in a cool place (Marinov 1964: 62). The master cheesemaker was often a businessman from the city (Marinov 1964: 70).

One of the most important products made from sheep milk is sirene, a fresh white cheese similar to the Greek feta. It was manufactured in multiple forms, most typically for the Karakachans tulumsko sirene and sirene stombotiri. Tulumsko sirene was a durable type of cheese aged in a sheepskin pouch. This pouch was shaped like a skinned sheep with tied-off openings for the animal’s legs. The wool was sheared very short from the skin, the bag was inverted to put the sheared fur on the inside, and the sirene was placed inside of it. This made it appropriately stored for transportation. Sirene stombotiri is an early stage of kashkaval: a hard, durable type of cheese. Also made from sheep cheese was the aforementioned kashkaval, farmer’s cheese, butter, and yogurt (Marinov 1964: 58–62; Nešev 1998: 30). The whey was later used as feed for dogs, or pigs in areas where pigs were kept (Marinov 1964: 56).

Karakachan sheep are also a source of strong, rough wool that was used to make rougher fabrics, tarpaulins, blankets, sacks, ropes, and rucksacks (Marinov 1964: 80). The sheep were sheared once a year: the shearing took place gradually during the warm summer months, and if the wool was shorn during the transfers between summer and winter pastures, it was sold on the spot. One shepherd was capable of shearing an average 10–30 sheep daily. Processing the dark wool of the Karakachan sheep – washing, dying, spinning, and weaving or knitting – was exclusively women’s work. The Karakachans even used their own simple type of loom, whose legs were firmly stuck into the earth inside the residential hut. During their transfers, they brought only the most important parts of the loom with them and made the remainder again in their new location (Marinov 1964: 77).

Women were not allowed to participate in the shearing, along with many other work activities around the sheep (Marinov 1964: 72; Markowska 1962: 235). Sheep had a prominent position in the Karakachans’ symbolic system; they were considered divine animals. Not only was the privileged work around sheep inappropriate for women, but during certain periods, for example during menstruation (Campbell 1964: 26–35) and pregnancy (Pimpireva 1995: 48), women were even forbidden from approaching the sheep. For the sheep, women represented danger, especially during the periods when their reproductive capacity was made in some way visible, because sheep did not belong to the women’s sphere (Campbell 1964: 26–35). (…)

The Karakachans also kept goats, but in substantially smaller numbers than sheep; a larger proportion of goats in the herd could thus indicate loss of prestige for the whole group (Campbell 1964: 31). In the Karakachans’ symbolic system, goats are demonic animals characterized by their insatiability and cunning, belonging conceptually to the women’s sphere, because all activities around goats were always carried out by women and activities around sheep, again, by men. An exception was grazing a herd of goats far from home, which was incompatible with domestic duties. Otherwise, however, exchanging these spheres meant shame and disgrace, for example when a man was seen milking goats (Campbell 1964: 26–35). The only man who could watch a herd of goats was a young man before his military service – that is, a man who had not yet accumulated a substantial amount of honor which he could lose by doing this (Campbell 1964: 26–27). Women milked the goats regularly, brought the milk to the dairy for sale, and collected dung for sale to lowland farmers (Campbell 1964: 31). They then made tarpaulins with goat hair, which was thought to give greater protection from the rain than sheep hair. These protected the Karakachans from the rain during their transfers, despite their potential to contaminate since they were made from “demonic material”.

Another important animal for the Karakachans’ survival was the horse. Horses served not just for transporting household goods between winter and summer pastures, but also for carrying milk to dairies or prepared dairy products to market. However, donkeys were used even more frequently for this purpose than horses. Donkeys also had a special role: namely, to carry food to shepherds isolated high in the mountains with herds of barren ewes and rams (Marinov 1964: 56). The Karakachans compensated for the quite high costs of keeping horses by renting them to farmers during the summer for various kinds of seasonal work. This work was often paid with grain (Marinov 1964: 54; Nešev 1998: 12).

In some places, the Karakachans also kept pigs. These, unlike the other domestic animals they kept, are less hardy and would not be able to manage the demanding transfers together with the herds. Accordingly, the Karakachans generally kept pigs only in their summer settlements and always slaughtered them before transferring to their winter sites. They dried the meat with salt in the dry mountain air to make pastarma (Marinov 1964: 56), a traditional, time-tested method of conserving meat in the Balkans very similar to Italian prosciutto. Even more often than pigs, the Karakachans were involved in poultry farming. Poultry, by contrast, was most often kept at the wintering sites (Marinov 1964: 56–57; Nešev 1998: 19) and sometimes carried upside-down with legs tied together on the saddles of horses. The eggs were used for both home use as children’s food and barter in the village. Eggs and goat products were often the only source of income exclusive to individual women (Campbell 1064: 32–33).

Published in: Gabriela Fatková, Karakachans in Bulgaria – A Pastoral History, Lidé města / Urban People 13/2011, 1, Faculty of Humanities, Charles University, Sofis, Prague, 2011, pp. 59–65.

Translation: Guy Tabachnick

References:

Campbell, John K. 1964. Honour, Family and Patronage. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kalionski, Alexei. How to be Karakachan in Bulgaria? [online]. [cit. 2009-06-16]. Available at WWW: >http://www.cas.bg/uploads/files/Sofia-Academic-Nexus-WP/Alexei%20Kalionski.pdf<

Marinov, Vasil. 1964. Prinos kăm izučavaneto na prizchoda, bita i kulturata na Karakačanite v Bălgaria. Sofia.

Markowska, Danuta. 1962. „Kilka uwag o procesie zanikania nomadskich migracji pasterskich na terenie Bułgarii.“ Ethnografia Polska 1962, 7: 226-239.

Nešev, Georgi. 1998. Bălgarskite Karakačani. Makedonia pres.

Pimpireva, Ženja. 1995. Karakačanite v Bălgaria. Sofia: Universitetsko izdatelstvo Sv. Kliment Оrchidski.

Urbańska, Barbara. 1962. „Karakaczani. Nomadski lud pasterski na bałkanach.“ Ethnografia Polska 1962, 7: 203-225.

Footnotes

1

“The liberation” in Bulgarian literature always refers to the Treaty of San Stefano, which ended the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). After this treaty was signed, Bulgaria’s independence was restored. Today Bulgarians celebrate this event as a national holiday (March 3).